The US 700MHz auction: truckloads of cash, but…

April 15, 2008

With the recently concluded US 700MHz auction raising USD19.1 billion – almost double the reserve price of USD10 billion – national administrators must be wondering what level of revenues could be achieved in their own markets.

The 700MHz spectrum in the US will be vacated with the transition from analogue to digital television, switchover being scheduled for 17 February 2009.

The auction was for five blocks, with all blocks except D Block being divided into various geographical splits of the national footprint:

- A Block – 176 “economic area” licences for 2 × 6MHz

- B Block – 734 “cellular market area” licences for 2 × 6MHz

- C Block – 12 “regional economic area grouping” licences for 2 × 11MHz, with "open platform" conditions

- D Block – single national licence for 2 × 5MHz, with conditions requiring a public/private partnership to create a public safety broadband network

- E Block – 176 economic area licences for 6MHz (unpaired).

Exhibit 1: 700MHz spectrum reserve prices and highest bids [Source: FCC]

| Block |

700MHz bandwidth

(MHz) |

Reserve price

(USD million) |

Highest bid

(USD million) |

Reserve price per MHz

(USD million) |

Highest bid price per MHz

(USD million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A |

12

|

1807.4

|

3961.2

|

150.6

|

330.1

|

| B |

12

|

1374.4

|

9144.0

|

114.5

|

762.0

|

| C |

22

|

4637.9

|

4748.3

|

210.8

|

215.8

|

| D (unsold) |

10

|

1330.0

|

472.0

|

133.0

|

47.2

|

| E |

6

|

903.7

|

1266.9

|

150.6

|

211.1

|

So what are some of the outcomes that may be of interest to other national administrators considering potential options for this spectrum?

- lack of interest in a public safety broadband network

- operators value the opportunity to retain the “walled garden” model

- absence of a new national player.

To a large extent, these issues have been influenced by characteristics of the US market, which may not necessarily be relevant elsewhere. We need to examine each in more detail to determine whether or not these findings are likely to hold in other markets.

Public safety broadband: a non-event

The FCC’s objective for the D Block licensee was to create a public/private partnership for a nationwide interoperable broadband network for state and local public safety users, which would be shared with commercial users. The D Block licence would be awarded to the winning bidder only after it entered into an FCC-approved network sharing agreement with the public safety broadband licensee.

D Block attracted only a single bid of USD472 million – significantly short of the USD1.33 billion reserve price – and thus the block remained unsold. This spectrum will not be immediately re-auctioned; instead the FCC will be “considering its options”.

Reserve prices for all spectrum blocks were published prior to the auction and were based on the auction prices for Advanced Wireless Services in the 1710-1755MHz and 2110-2155MHz bands (“AWS-1”). For D Block, a discount of just under 25% was applied to the benchmark reserve price, to compensate for the rules and obligations imposed upon the D Block licensee. The FCC considered that these estimated values were conservative, due to the more desirable characteristics of the 700MHz band as compared with AWS-1.

In a subsequent investigation by the FCC, a number of factors were identified which created huge risk for the commercial operator, and ultimately deterred potential bidders:

- uncertainty over the technical specifications of the public safety broadband system and thus the level of funding requirements

- quality of service for the public safety network was considered to be much higher than that required for commercial use, which would increase costs

- the priority access regime for public safety users – whereby the commercial operator would have access to the network on a preemptible basis – diminished the commercial value of the network

- the network footprint would need to be extensive, in order to reach all public safety users

- revenues were uncertain as there was no requirement nor guarantee that public safety users would subscribe to the network

- the high risks involved if the successful bidder was unable to negotiate a satisfactory network sharing agreement with the public safety broadband licensee – due to the bid default penalties that could be imposed on the winning bidder, the public safety broadband licensee had far greater leverage in negotiation proceedings. There may also have been a perception that the needs of public safety would receive preferential treatment in arbitration proceedings.

Open platform: how Google nearly won spectrum it did not really want

The FCC imposed conditions on the C Block licensee to provide an open platform. That is, allowing a consumer to use whatever device or applications they want, subject to reasonable network management conditions to protect the integrity of the network.

If the highest bid for C Block failed to meet the reserve, the FCC would then re-offer C Block in a subsequent auction, but without the open platform conditions.

The FCC’s open platform requirement fell somewhat short of the “open access” model supported by Google, Frontier Wireless and other players. Under this model wholesale access to the wireless network would be available to competitors – similar to the situation for wireline networks. Nonetheless openness in relation to handsets and applications represents a major development for the US market.

For a number of years, US consumer groups have been lobbying the FCC to ban handset locking, which has been widespread in the US on both CDMA and GSM networks. There have been several recent lawsuits brought by consumers against wireless carriers challenging this practice. In October 2007 Sprint Nextel settled a class action lawsuit brought by consumers under California state law, in which the carrier agreed to disclose phone lock codes, assist customers to activate non-Sprint Nextel handsets on the carrier’s network and notify retailers of these policies. A similar settlement was made with Verizon Wireless, although the carrier denied locking handsets.

While unlocked phones have been available, these are not subsidised. Consumers’ price expectations have been influenced by the heavily subsidised handsets available through the carriers – thus full price phones are less attractive to the price-conscious. Even if consumers purchase an unsubsidised, unlocked handset, there is no guarantee that it will operate on their chosen carrier’s network, as the carrier may tightly control what devices and applications are permitted to be used. On carrier-supplied devices, it is not unknown for standard handset features to be turned off and applications disabled.

Google had previously indicated its commitment to open broadband platforms, through its submissions to the FCC. So, Google’s strategy was to force prices for C Block to reach that all-important reserve – even to the extent of outbidding its own bids – with its final bid of USD4.71 billion just exceeding the reserve price (USD4.64 billion).

Ultimately Verizon Wireless captured C Block, with a winning bid of USD4.75 billion.

In terms of the highest bids, the C Block price per MHz was substantially lower than that for A and B Blocks, and only marginally more than the unpaired spectrum in E Block (Exhibit 1). Any advantages that may have been attributed to the larger geographic areas or the larger block size were negated by the open platform conditions.

The US operators clearly placed a significant premium on the ability to control both the devices that users employ to access the network, and the applications that users are permitted to run. So the question regulators need to answer is whether the consumer benefits of open platforms are greater than maximising spectrum revenues by permitting licence holders to control how consumers access and use their networks.

It will be interesting to see how the open platform will fare in practice. The interpretation of “reasonable network management conditions” could allow Verizon to have considerable latitude in controlling what devices and applications may or may not be used.

What happened to the new entrant?

Prior to the auction, the FCC’s Chairman hoped that a “third pipe” – a new national wireless broadband competitor to cable and DSL – would emerge, however the auction confirmed the ongoing dominance of the two largest US mobile operators: AT&T and Verizon Wireless.

The two companies’ winning bids comprised over 80% of the total. The third and fourth largest operators – Sprint Nextel and T Mobile – did not bid in the auction. The fifth largest player – Alltel – did participate, but was not successful. New players did emerge in rural areas, and Frontier Wireless – owned by the satellite television provider EchoStar – purchased 168 of the 176 licences in E Block.

Exhibit 2: Mobile market share, 2006 [Source: FCC]

It should be noted that while the top four US operators are commonly described as “nationwide”, in fact they have differing geographic footprints. In addition to the top four carriers, there are several large regional players (including Alltel, Leap Wireless and US Cellular), and numerous small operators.

Any vision of a new entrant competing with wireline broadband players would have been incredibly optimistic. Compared with wireline, the largest block – the 2 × 11MHz C Block – just does not offer sufficient data-carrying capacity. However, beyond the reach of DSL and cable, where population density (and traffic demand) is lower, it may have enough capacity to provide residents with broadband services.

Perhaps the FCC assumed that criticism of the open platform requirements by major players – including AT&T and Verizon Wireless – indicated that they would leave C Block to be snapped up by a new entrant.

Alternatively, it could be argued that the FCC’s high per-MHz reserve price for C Block created a barrier for new nationwide entrants.

If the FCC’s intent was to encourage greater diversity in the market, then the bidder eligibility rules should have been more explicit, which would probably have affected the end price paid. The question for regulators is whether this risk is outweighed by the benefits of increased market diversity.

You’ve got to have it to sell it

Of course this opportunity can only be realised if existing users will be relinquishing the spectrum. In most cases the spectrum is being released when countries make the switch from analogue to digital television, which is happening progressively around the world over the next seven years.

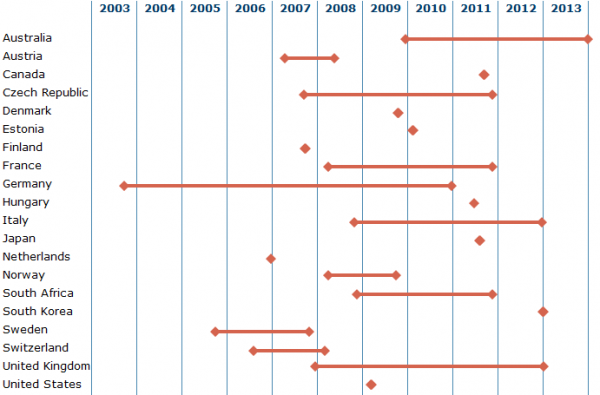

As at April 2008, analogue switchover (ASO) has been completed in the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland. In countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom and Norway a programme of regional ASOs is underway. ASO schedules are planned for many other countries, some with a phased regional approach and others with a single national cutover date (Exhibit 3). In some countries, the ASO date will be set once certain market conditions are reached; for example New Zealand will set a firm date for ASO when digital TV take-up is 75%.

Exhibit 3: Planned analogue switchovers for selected countries [Source: national administrations]

Delays in ASO plans have not been uncommon. Australia planned to switch off analogue TV over the period 2008 to 2011, but ASO has now been postponed with final switchover now expected by the end of 2013. Other countries that have put back their scheduled plans include the Czech Republic (delayed one year to 2011) and Italy (originally 2006, then 2008, now 2012). In contrast, ASO has been brought forward in some countries, including Estonia (two years earlier) and Hungary (one year earlier).

Could the freed 700MHz spectrum achieve similar returns as in the US auction? As we have seen in other auctions, not only the telecoms market characteristics but also the overall economic environment are key influences on bids and bidding strategies. Timing is everything.